Research & Process: Arirang Mass Games

I have attempted to present the realities of life in current-day North Korea as accurately as possible based on the present available information. (By the time the book is in print, some of what I have written may already be outdated.)

But I have also made a few decisions in service of my story. For instance, the Arirang Mass Games have not been held since 2013, but I included a performance here, because the scale, organization, and presentation of the event is a uniquely and definitively North Korean phenomenon.

Read MoreReaders & Educators: Tracing the Journey

Plotting IN THE SHADOW OF THE SUN with Google Earth Maps

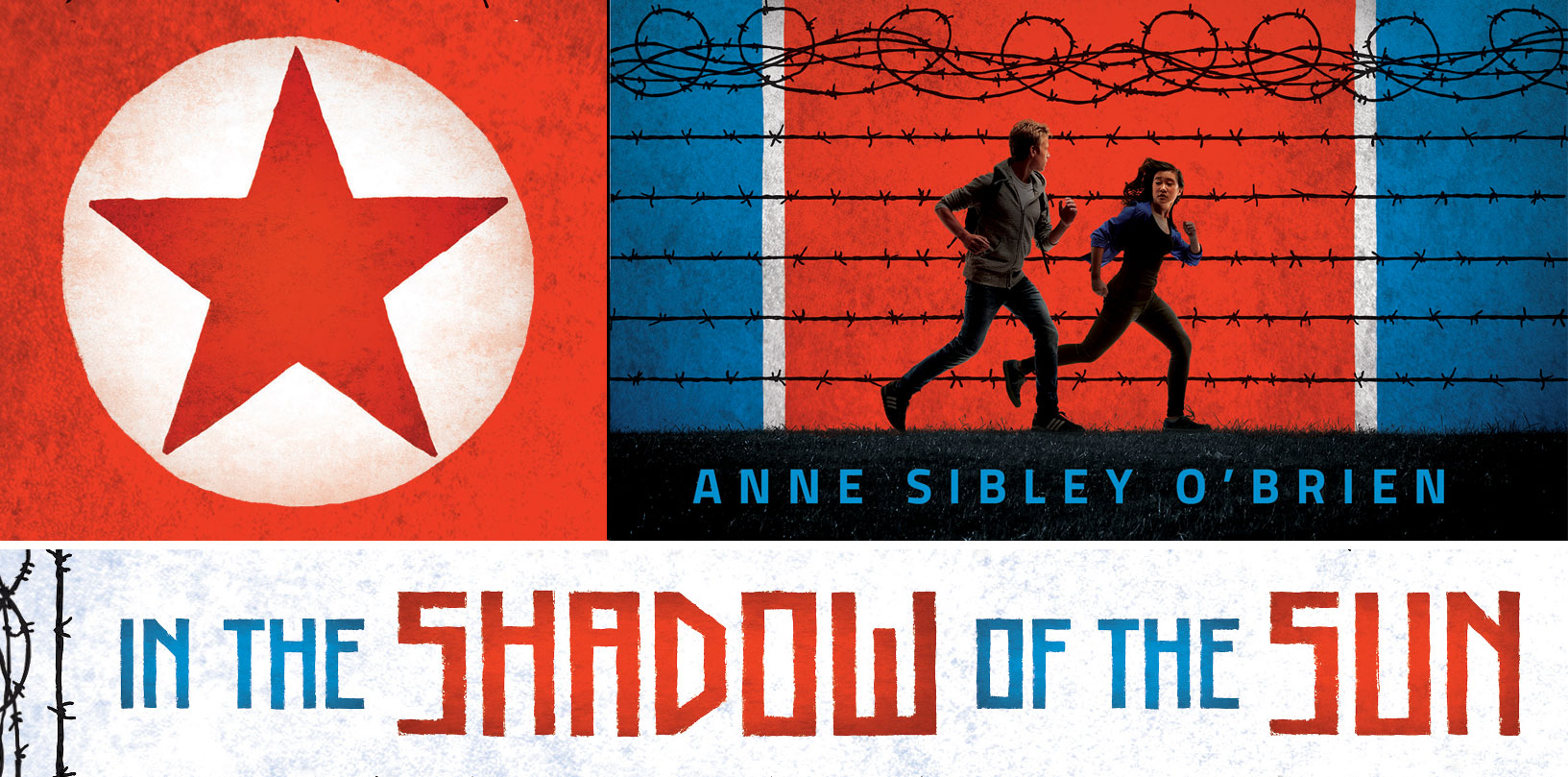

It’s possible to trace Mia and Simon’s entire journey in In the Shadow of the Sun.

I plotted it on Google Earth as I was researching and writing it.

Note that I did add the stairs down which they escape at Mangyongdae, and the park along the river in Sinuiju.

Read MoreCultural Advisors for In the Shadow of the Sun

Throughout the development of In the Shadow of the Sun — and the thirty years of our life together — our beloved daughter, Yunhee, has shared her experience of being a transracially adopted Korean American.

Throughout the development of In the Shadow of the Sun — and the thirty years of our life together — our beloved daughter, Yunhee, has shared her experience of being a transracially adopted Korean American.

I had personal connections to several people who had deep knowledge of North Korea and were willing to read my manuscript. For other expert readers, I contacted two Korean American organizations with which I’ve had previous contact, Korean American Story and the Council on Korean Americans.

I am enormously indebted to those who provided expert and essential feedback on the final draft (a number of whom choose not to be named for fear of difficulties if they return to the DPRK):

Cultural Advisors

1) A, an international observer of North Korean affairs who travels frequently to the DPRK;

2) D, a foreign resident of Pyongyang, for detailed information about city life;

3) SJK, who taught English in Pyongyang, for a Korean American perspective on North Korea;

4) David McCann, Korea Foundation Professor of Korean Literature, Harvard University, who has traveled to the DPRK four times and lectured there;

5) Seongmin Lee, who was born and raised in North Korea and escaped as a young adult;

6) J, who was also born and raised in the DPRK, and escaped at a teenager; and

7) An expert on Korean transracial adoption.

These readers corrected many mistakes and misimpressions and challenged me to go deeper into the material. There were notes on history (don’t refer to the Chosun Dynasty as “unifying” the peninsula, as the Silla Dynasty did that first), tourism (which currencies are used when, by whom), contemporary life in Pyongyang (many ordinary families don’t have running water, even in city apartments), political realities (officials would not be likely to identify themselves as from the Ministry of Peoples Security; security checkpoints are frequent). One of my experts even knew that the knock-off of “Angry Birds” that’s used by North Koreans is in Korean, not Chinese!

These experts also caught a number of crucial errors that were based on my South Korean experience instead of accurate to North Korea. For instance, I had learned that North Koreans refer to Korea as “Chosun” and Korean language as “Chosun-mal.” But having grown up calling Korea “Han-gook” and Korean language “Han-gook-mal,” as they do in South Korea, I had inadvertently used that in the manuscript.

The adoption expert responded with challenging and penetrating questions that caused me to reflect more deeply on Mia’s experience of being transracially adopted and the particular ways in which she and her family members lived that reality.

Any remaining errors of fact or interpretation are my own.

The responses of these expert readers was also sometimes deeply affirming. One of the questions I carried throughout the writing of this book was about my choice to write about North Korea through the lens of two Americans. To what extent might that be exploiting or marginalizing the lives of North Koreans? At the same time, I remained convinced that young readers outside of North Korea would respond to characters who could provide a bridge from their world to that of the DPRK.

I was amazed and humbled to read this note from one North Korean defector:

“Through the courageous, brave characters of Mia and Simon, their journey, and your vivid narratives, I was amazed while reading your work and found my memories awakened, and my senses redolent, as if I were once again in North Korea.”

I met one of the most important influences on this book in 2010, at the invitation of my friend Yoo Myung Ja. She introduced me to Professor Kim Hyun-Sik, formerly one of North

I met one of the most important influences on this book in 2010, at the invitation of my friend Yoo Myung Ja. She introduced me to Professor Kim Hyun-Sik, formerly one of North

Korea’s foremost educators, and the personal Russian tutor to the teenage Kim Jong-il. In 1991, while working in Moscow, Professor Kim was approached by a South Korean agent with the astonishing news that his sister, whom he hadn’t seen since the Korean War and had long thought dead, was alive and waiting to meet him. A double agent reported their reunion to the DPRK, and Kim was forced to make the excruciating decision between returning home to face certain death, or defecting, knowing his entire family in North Korea would be killed. He spent a number of years in South Korea before moving to the US, where he served as a research professor at George Mason University.

(You can read Professor Kim’s account of his years in North Korea, the circumstances of his defection, and his life since in this article.)

Throughout the hours of our conversation over several days, Professor Kim, a gentle, soft-spoken man, was often in tears recalling the struggles of his former countrymen.

He was the first North Korean defector I’d ever met, and he told me I was the first white American with whom he’d had such a personal encounter. “They told me you were my enemy,” he said. I shared my book idea with him and asked what he would hope to see a novel about his homeland accomplish. “To create empathy for the North Korean people,” he said. In the course of writing In the Shadow of the Sun, this has become my hope too.

Glimpse of North Korea

While I was writing In the Shadow of the Sun, I traveled to Dandong, China, where I was thrilled to discover that my hotel room window faced the Yalu River with a view of the city of Sinuiju.

I took a motorboat ride through the waters that separate the two countries, and traced my charcaters, Mia

and Simon’s steps up a section of the Tiger Mountain Great Wall. There, I sat and gazed at “One-Step Crossing” and the North Korean countryside.

Read the post I wrote about that trip.

Read MoreHow I Came to Write This Book

Writing this novel has been a ten-year journey of research, hard work, conversation, and reflection, especially on the subject of identity. I’m a white American whose own identity was profoundly shaped by moving from New Hampshire to South Korea in 1960, when I was seven years old. Korea, where my parents worked as medical missionaries, was our family’s home base for twenty-one years.

I speak fluent conversational Korean, spent my junior year of college at a Korean university, and have returned to Korea many times throughout my adulthood. Korea is “home” to me, even as my connection remains that of an outsider-insider. But prior to this book, my sphere of personal knowledge, experience, and interest in Korea had never included the North. Even when I was a child and teenager in South Korea, the country occupying the other half of the peninsula seemed unknowable, foreign and menacing — a feeling exacerbated by the bellicose threats and posturing of the DPRK, and its 1968 assassination attempt on South Korean President Park Chung-hee.

Ten years ago, a chance interview question about reunification led to the idea for a novel about two American kids on the run in North Korea. I did some reading and daydreaming, but I felt uncertain about my connection to the material until I met Reverend Peter Yoon, a member of the Council on Korean Studies of Michigan State University. In 2007 he had traveled into the DPRK from China by train and had an hour and a half of video footage of the countryside between Sinuiju and Pyongyang. The images were spellbinding, and to my surprise, they were familiar.

Rural North Korea in 2007 — wide plains filled with rice fields, farmers planting in flooded paddies, people pushing carts and riding bicycles, clunky concrete apartment buildings painted pink and blue — looked exactly like the South Korean countryside of the 1960s where I grew up. I realized the DPRK was not unknowable and foreign; despite its government, it was part of a land I knew and loved. Over the years of research and writing that followed, North Korea came into focus more and more as a place of enormous complexity and contradiction, and most of all a place full of real people.

Indeed, contrary to the popular image of a country shrouded in mystery about which we know almost nothing, I’ve found an extensive amount of information available about the DPRK.

More About Growing Up in Korea:

Of Longing and Belonging (Korean American Story)

Considering North Korea (Korean American Story)

China!

There’s a Chinese folk tale, variously called “Fortunately, Unfortunately,” or “That’s Good! That’s Bad!” A farmer loses his horse – bad fortune! But soon the horse returns, with a stallion – good fortune! The farmer’s son is thrown off the stallion and breaks his leg – bad fortune! But then military officers arrive in the village to conscript every able-bodied man and the farmer’s son isn’t taken because of his leg… And so on.My five-day solo trip in China felt like a version of this tale. The first piece of seemingly bad fortune was the discovery upon arrival in Beijing that the reservation confirmation receipt for my Chinese hutong inn (a hutong is an alleyway or narrow side street) didn’t have enough information on it for the average Chinese person to be able to tell where it was located. The good fortune was finding one person after another, most of whom didn’t speak any English – and I speak no Chinese – to help piece together the next step of my journey, from airport to express train to subway to street. My final angel of mercy was Peng, who did speak some English and told me to call him Elton. He helped me with my heavy luggage, guiding me down the correct street to the front door of the inn, a welcome sight.

We exchanged enough information, with the help of my iPad photos, to discover that the city my grandfather grew up in in the early 1900s is Elton’s hometown! To have bumped into each other in one of the largest cities in the world seemed quite remarkable.

My grandfather, Horace Norman Sibley, center, with his parents and sisters, approx 1906.

The next day was a trip to the Great Wall, which I’ve wanted to see ever since I painted it for the book Talking Walls by Margy Burns Knight.

I’d chosen a tour to the Mutianyu section of the Wall, supposed to be one of the most scenic. I spent the day with an international group of tourists from Pakistan, Canada and the Philippines, our driver, and our guide, a young woman called Eva. Eva is married, with a 2-year-old son, and commutes two hours each way from her suburban apartment, because housing closer to the city center is unaffordable. The tour included some Ming tombs, a jade factory, lunch in a restaurant at the foot of the mountain (about an hour northeast of Beijing), and finally, the Wall!

No photos can do justice to the scale and sheer magnificence of the Great Wall. Seeing the height and steepness of these rocky mountains, it stuns the mind to think of the engineering feat that created this Wonder of the World – and of the millions of lives lost in its construction. The Wall is so high up that almost everyone opts for the cable car or chairlift up – with the option of a tobbagan ride down! It’s a real physical workout, just ascending and descending the stairs and walkways on top of the Wall itself.

Saturday I flew to Dandong, on the northern banks of the Yalu River, which forms the border between China and North Korea. In addition to growing up in South Korea, for the last eight years I’ve been working on a young adult novel set in North Korea. (The day I was leaving on this trip, I received some very exciting news about this novel – TBA in a future post!) I wanted to travel to this part of China to trace the steps of my fictional characters, who in the book’s climax end up on a section of the Great Wall, called Hu Shan (Tiger Mountain), not far from Dandong.

I was tremendously excited to discover upon arrival that my 6th floor hotel room looked out over the Sino-Korean Friendship Bridge and the North Korean city of Sinuiju, barely visible in the smoggy mist:

A North Korean village on an island in the Yalu River. We are traveling between the island and mainland DPRK – clearly in North Korean waters. The woman herding goats waved and smiled when I called hello to her in Korean.

When I did finally get out of the taxi on the way back to Hu Shan, the entrance to the Wall was indeed closed; inside, a grounds crew was gathering and burning brush. Exploring around the edges on my own – including scrambling up one steep slope, hanging onto branches to keep from slipping in the sandy soil – I stumbled upon paths and views that I never would have found if I’d been on top of the Wall.

And on the south side, there is no gate!

I was able to climb part way up the Wall, just as I’d imagined, and sit to paint a panoramic view of the North Korean countryside.

All in all, an amazing adventure, full of good fortune!